General News

Meropi Kyriacou Honored as TNH Educator of the Year

NEW YORK – Meropi Kyriacou, the new Principal of The Cathedral School in Manhattan, was honored as The National Herald’s Educator of the Year.

Part 3: The Alchemy of Greek Assimilation in America

Read Part 1 Here

Read Part 2 Here

In 2022 Hellenism both continues to mark the Greek Bicentennial, whose celebration was interrupted by the pandemic, and the aftermath of the Greek Revolution – which includes the Asia Minor catastrophe and the mass migration of Hellenes to America, a place where they were not always welcome.

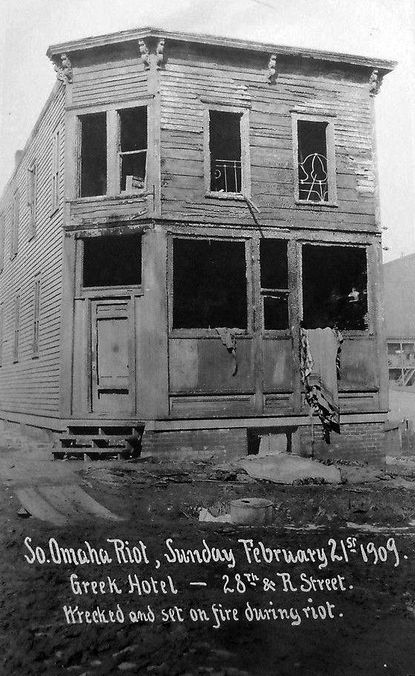

With this in mind, in a series of four articles we are addressing the anti-Greek riots in Omaha in 1909, which led to the persecution of the Greek community of the time.

As was detailed in Part I, the riots erupted when a Greek immigrant, John Masourides, killed a police officer, Edward Lowry, who had arrested him on the then-widespread charge of vagrancy.

The assassination of police officer Edward Lowry by John Masourides became an opportunity to express, in criminal fashion, Americans’ anxiety over the Greeks’ presence.

In Part I James Bitzes, a retired U.S. Air Force Colonel, spoke about his personal research in journalistic and other archives, offering Hellenism a timeline of these important events.

In Part II we talked to distinguished History Professor Nelson Lichtenstein, who heads the Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He addressed issues like the perceived and felt ethnic identity of the Greek immigrants and their place in the labor market that drove both their immigration and the responses of their American neighbors.

In Part 3 we speak with Peter Moskos, who, with his father, the renowned sociologist Charles Moskos, wrote Greek Americans: Struggle and Success, a book which is one of the most important recent accounts of Greeks’ migration to the United States. A professor in the Department of Law, Police Science, and Criminal Justice Administration at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and the best-selling writer of Cop in the Hood and In Defense of Flogging, Peter spoke to about the elements that determined Greek immigrants’ integration in American society.

The National Herald: Were some cities more welcoming or promising than others for Greek immigrants? What made them so?

Peter Moskos: I think that, where Greeks followed Italians, they had an easier job of settling in; and, where they sort of moved in as the first swarthy, Mediterranean, not-quite-white group, they faced more opposition. I’m guessing. Certainly, more is written about the Irish, but I think that other immigrant groups who came during that era, even if they weren’t from Ireland, paved the way. The average xenophobe probably couldn’t even tell the difference between an Italian and a Greek. And the Greeks tended to move to Italian neighborhoods, taking over a lot of the kind of work Italians were doing. In many ways they may have just got in under the radar in the big cities. Also, Greeks often talked about returning back home. Most didn’t, but some did. I suspect that the work gangs out west were more transient, literally – and also sort of spiritually – and that probably mattered, too. If you get people who are migrating to work on the railroads, or do whatever, there’s less of a “we’re here to stay forever” mentality, and it compounds the language issue and so on. Those communities probably were more transient or more temporary, or more male, which makes them rowdier and more violent. Let’s not forget that some of the opposition was rooted in reality. Not that that justifies it, but they weren’t all angels, right? When women started coming, it was in established communities with churches, older communities, and it probably had a very civilizing effect. It made the Greeks seem more normal to the Americans.

TNH: So, women changed the perceptions.

PM: Well, yes – once you settle down with a family life, the perception changes. There’s less carousing and hanging out late, drinking, and listening to that ‘exotic’ music.

TNH: Was it that Americans had been acculturated to the presence of immigrants through the Italians, or did Greeks and Italians share some characteristics that helped?

PM: This can actually be somewhat supported with the data I provide in my book about intermarriage: there’s a lot of feeling -right or wrong – that Greeks and Italians and Irish have similar values: In terms of family, in terms of a certain degree of religious faith. There always has been a lot of intermarriage between Greeks and Italians, and Greeks and Irish. I mean, there could have been riots between Italians and Greeks; they didn’t happen. But, in a counterfactual world, it’s sort of interesting it didn’t happen, because they’re competing for the same resources. You’ve got the slightly more established Italians and the newcomer Greeks, and it could have led to big gang fights. I don’t know a single account of that actually happening. I don’t know why it didn’t happen, but both were then put in a position of being in opposition to WASP-y culture.

TNH: You mention religion. What were the traits of Greek immigrants that most helped their incorporation, and what were those that most impeded it?

PM: The Greeks had a huge step up in that they were generally literate. I’m talking about grade school education, but, still, they could read and write. That’s a big step up, compared to the average peasant that came over from other parts of Europe. And, thanks to the Ottomans, they had a capitalist business savvy that Irish serfs on somebody else’s land simply didn’t have. Economic success goes a long way to acceptance.

TNH: What about the actual geography of immigration? Was that defined by whomever brought in the Greek immigrants, or was it a process of trial and error?

PM: A lot of it was really a strange matter of luck. You had an uncle somewhere, so you went there. That’s the only reason my family ended up in Chicago. If you didn’t know anybody, then, maybe, you ended up further out west, because some padrone was promising you a job that may or may not have existed, or existed, but not in the way that he was promising it. But, for all these somewhat close-knit communities and sense of family, a lot of people wanted to get away. People rarely talk about that, because they want to emphasize the positive.

TNH: What were the Greek immigrants’ relations with other immigrants? Was there a sense of solidarity, or was the competition for work and assimilation too big an obstacle?

PM: It seems that there was solidarity. With the exception of the union scabbing – that part was real. But in terms of going into restaurants and florists and confectionaries and fruit stands, it seems like it was a pretty peaceful transition from mostly Italian to Greek, in the same way a lot of Greek and Italian pizza joints have been taken over by Albanians, but peacefully. It’s not like that was a big conflict. It was simply “oh, you are a good worker, and I want to get out of this business, and it’s tough, and you still got the energy, as a recent immigrant.” So, my guess is it followed more of that model.

TNH: And did that lead to local societies’ acceptance? I’m guessing they were treated better than Greeks who had stayed in railroad work and so on. So, was getting in such lines of work a way to overcome this distrust against people who the context of the Omaha riots were described as “disease-ridden, dirty Greeks,” who did not even amount to a ‘white person’?

PM: Well, the Irish had the advantage of speaking English. That helps, especially outside the mining and railroad industries. But even then, they did end up settling down. And the general trend in the Greek community was one of assimilation. Not complete assimilation, of course, but that idea that “we’re American.” AHEPA probably was a significant factor. It brought the idea that we can have Greek identity, but it was very much in the mentality “we’re going to say this is our home, and we are going to fit in here. We’re not expats that might go home. This is our final destination.” Of course, the church is a major factor, too, but I can’t figure out how that is unique from any other group.

TNH: Still, the United States were not happy to get Greek immigrants.

PM: Yeah, they were part of the huddled masses. I always want to deemphasize the “the Greeks had it worse,” sentiment because I don’t think they did. Maybe they did. Maybe it was better for Scandinavians and Germans, but even the Germans faced a lot of opposition in cities, as they took over control of local political machines. Some of it no doubt is just straight up racism, I suppose. Perhaps. You know, someone from Norway, for example, is just whiter, and the Greeks were swarthy and oriental. So that obviously had some effects. But even the anti-Greek riots and pogroms that happened, even though they were explicitly anti-Greek, it doesn’t actually seem the Greek part was the issue. It was the foreign part, the ‘different’ part.

NEW YORK – Meropi Kyriacou, the new Principal of The Cathedral School in Manhattan, was honored as The National Herald’s Educator of the Year.

MELBOURNE, Australia (AP) — More than 100 long-finned pilot whales that beached on the western Australian coast Thursday have returned to sea, while 29 died on the shore, officials said.

On Monday, April 22, 2024, history was being written in a Manhattan courtroom.

PARIS - With heavy security set for the 2024 Paris Olympic Games during a time of terrorism, France has asked to use a Greek air defense system as well although talks are said to have been going on for months.

PARIS (AP) — Paris has a new king of the crusty baguette.

WASHINGTON (AP) — A tiny Philip Morris product called Zyn has been making big headlines, sparking debate about whether new nicotine-based alternatives intended for adults may be catching on with underage teens and adolescents.