General News

Meropi Kyriacou Honored as TNH Educator of the Year

NEW YORK – Meropi Kyriacou, the new Principal of The Cathedral School in Manhattan, was honored as The National Herald’s Educator of the Year.

The establishment of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America in New York City 1922, under the name Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America, was a very important turning point in the history of Greek Orthodoxy in the New World. It signaled the beginning of a more organized church life under the auspices of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. From that moment onwards, the Archdiocese was the spiritual and administrative head of the Greek Orthodox Church in North and South America until 1999, and after that, with the creation of separate bodies for Canada, Central America and South America, the Archdiocese of America, as it was renamed, led the church in the United States.

The Beginnings of Orthodoxy in America

Orthodoxy had arrived much earlier in America, brought by early colonists in Florida and merchants based in New York and in New Orleans. It was in New Orleans where the first Greek Orthodox Church was established, thanks to a donation by Nicholas Benachi, one of several Greek cotton merchants in the city. In the meantime, Russian Orthodox priests had appeared in Alaska, a Russian province that became part of the United States in 1867. In 1868 a Russian Orthodox church was established in San Francisco and in a few years, it became the seat of the Russian Orthodox Diocese in America. Russian churches slowly began appearing throughout the United States. The congregations of most of those churches were multi-ethnic including not only Russians but also Slavs, Arabs, and Greeks.

In the 1890s the big wave of emigration from Greece to the United States began, caused initially by an agricultural crisis in Peloponnesos. Until the United States imposed restrictions on immigration from Southeastern Europe, including Greece, in the early 1920s, about 400,000 Greeks had arrived in America. While a number of them would return after a few years, more than 3 in 4 remained, and as the increasing number of women showed, thousands of Greek immigrants were deciding to stay permanently and create families and a community life in the United States. Wherever they settled the Greeks began to establish community organizations and churches. Indeed, the main purpose of the community was to administer the church which was in demand not only for the exercise of the faith but also for baptisms, weddings, and funerals. Where there were only a few Greeks they would worship in the local Russian church, but as soon as their resources allowed them, they established a Greek Orthodox church.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate held the jurisdiction over the Greek Orthodox church in the Diaspora, but in 1908 it passed on the responsibility for the Greek Orthodox in America to the Church of Greece. At the time, the Greek immigrants were forming churches with no connection to the Russian Orthodox Archdiocese in America. Instead, they were contacting the churches in their villages asking them to send a priest or a person who could serve as a priest in America. The Church of Greece was unable to control the situation – there were tens of requests and meanwhile priests and monks and a few unqualified persons traveled on their own to America seeking somewhere to offer their services. These early years of the presence of Orthodoxy in America confirmed the deep sense of religion of the early immigrants, it witnessed the work of many pioneer priests, but it also entailed anomalous instances with priests being either unprepared or unqualified to lead a Greek Orthodox parish in America.

The Establishment of the Archdiocese 1918-1922

It was the Metropolitan of Athens, Meletios (Metaxakis) who sought to achieve a better organizational structure for the church in America, and he traveled to the United States in 1918 to begin the process of creating a central administrative body. By that time there were over 150 parishes across the country. Thanks to Meletios’ efforts and leadership, a gathering of Greek Orthodox clerics in New York in 1921 decided to establish the Archdiocese of North and South America and elect one of Meletios’ associates, Metropolitan Alexandros (Demoglou) as the first Archbishop. At the end of that year, Meletios was elected Ecumenical Patriarch by the Holy Synod in Constantinople. One of the first things Meletios did was to reclaim the jurisdiction of Orthodoxy in America for the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and he then officially recognized the Archdiocese with Alexandros as Archbishop in America in April, 1922.

The Archdiocese consisted of four regional bishoprics, New York, Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco, with New York being the Archdiocesan seat. Meletios, in Constantinople, in planning the future of the Archdiocese was aware of the growing political divisions within the Church of Greece between supporters of the king and supporters of liberal politician Eleftherios Venizelos and was also aware of the rise of Turkish nationalism, which threatened the Ecumenical Patriarchate. For those reasons he granted a degree of autonomy to the Archdiocese.

Archbishop Alexandros (1922-1930)

The early years in the history of the Archdiocese were dominated by a situation that reflected Greece’s political divisions. It was an unfortunate characteristic that the ‘national schism’ between the pro-royalists and the pro-venizelists had poisoned all aspects of life in Greece and its Diaspora communities. Alexandros, was considered as a venizelist because he had been appointed by Meletios, who was closely associated with Venizelos. This meant that not all clergy and lay members of the church in America accepted his authority, and where they had sufficient power, they ensured that their parishes remained outside the Archdiocese. The situation became even more difficult when Metropolitan Vasilios (Komvopoulos) a pro-royalist cleric arrived in the United States and for a few years managed to establish an ‘autocephalous’ Greek Orthodox Church in the United States based in Lowell, Massachusetts with about 50 parishes, compared to the over 130 parishes that remained loyal to Archbishop Alexandros. The divisions in the Church in America began to heal only after concerted efforts of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the Church of Greece, and the Greek ambassador to the United States Charalambos Simopoulos. Alexandros was eventually persuaded to step down and he was replaced by Archbishop Athenagoras (Spyrou) the Metropolitan of Corfu.

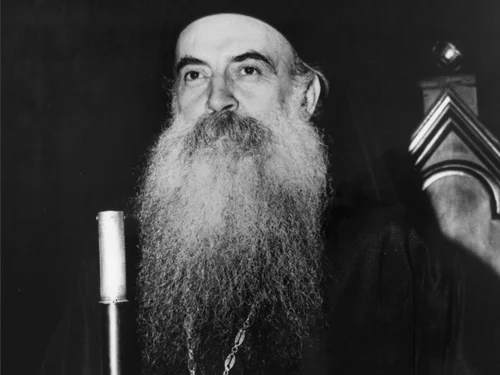

Archbishop Athenagoras (1931-1949)

Athenagoras’ arrival in New York in February 1931 meant the beginning of an era of growth and development for the Archdiocese and for Orthodoxy in America. The new Archbishop received an enthusiastic welcome by all of the Greek-American organizations and the two major daily Greek language newspapers, the Atlantis and the Ethnikos Kirix. The welcome indicated that the community wished to put behind it the divisions of the past and collaborate in order to preserve Hellenism in the United States. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the growing economic crisis affected thousands of Greek-Americans and the community leaders understood they had to focus on the more immediate issues created by the difficult economic conditions. Athenagoras, a charismatic and dynamic cleric, was able to unite all sides and inspire their confidence. One of the first things Athenagoras did was to travel to Washington, DC to meet President Herbert Hoover.

Over the next few months Athenagoras traveled throughout the country in order to familiarize himself with the state of Orthodox parishes and the issues they faced. He soon ascertained that the parishes had meager resources, that the abilities of the priests varied from place to place, and that the instruction in the Greek schools was mostly inadequate. In August of that year, he offered prayers and addressed the national convention of the largest Greek-American organization, the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association (AHEPA) in San Francisco. Although AHEPA, which was formed in 1922, had focused on the need for the Greek immigrants to Americanize, it was gradually embracing its Hellenic roots more and more openly. Athenagoras’ presence at its convention was the beginning of an increasingly close cooperation between AHEPA and the Archdiocese. Up to that point the Archdiocese had ties with the smaller and more Greek oriented organization, the Greek American Progressive Association (GAPA), which would limit its activities in the post-World War II era, in contrast to AHEPA which remained active and influential.

In November of 1931 Athenagoras was ready to introduce a wide-ranging set of changes in the life and the organization of Orthodoxy in America. The Archbishop convened the fourth general assembly of the Church, what is now known as the Clergy-Laity Congress. The opening day at the Evangelismos church in New York was attended by the ambassador of Greece, the Greek general consul in New York, representatives of all the major Greek-American organizations, and the Greek-American press. Those assembled witnessed a speech that was an elegant and emphatic statement, and one that would set the church on a course of change. Athenagoras presented three major sets of changes that he was proposing: the abolition of the Archdiocese’s autonomy from the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the strengthening of the Archbishop’s powers over the bishops, and ending the dependency of parishes on the local community organizations and thus making the parish self-governing under the supervision of the Archdiocese. The reasons Athenagoras gave for introducing those radical changes was that a closer relationship with Constantinople would enhance the standing of Greek Orthodoxy in America and make it the strongest of all Eastern Orthodox Churches, and that allowing more powers to the Archbishop would protect the Church from the local divisions it had witnessed in the past. He gave the same reason for what was essentially the reversal of the relationship of the parish to the local community organization, pointing to the negative political influence of lay members in church affairs, adding that too great role for the laity was a characteristic of Protestantism, not Orthodoxy.

It was the third of those changes, the enhanced role of the parish, that faced the most opposition by the leaders of several community organizations. When implemented it strengthened the parish because it assumed the responsibility to administer the local Greek schools and philanthropic activities. Within a couple of decades most parishes had absorbed the local community organizations. Now, as the main Greek-American organization, the parish ran the Greek schools and organized philanthropic activities through their Ladies Philoptochos groups. Both education and philanthropy were supervised by national committees formed by the Archdiocese. The growing significance of the activities of the Ladies Philoptochos over the decades that followed confirmed that women would play a role in the life of Orthodoxy in America.

As far as education is concerned, the truth is that it was and continued to be very difficult to address the needs of promoting and preserving the Greek language in the American environment. Measures taken to improve the pay and quality of teachers and to introduce appropriate educational materials always seem to have fallen short, with the exception of a few instances thanks to the hard work of enlightened teachers.

Athenagoras took several important steps in his efforts to strengthen the Church’s spiritual and educational life. In 1934 the Archdiocese began the publication of the Orthodox Observer, which appeared initially as a monthly magazine and several decades later switched to newspaper form and more recently to an electronic format. In 1937 the Archdiocese established a theological seminary, the Holy Cross Theological School in order to train priests that would serve in parishes throughout the Americas. It opened in Pomfret, Connecticut and in 1946 it moved to Brookline, Massachusetts. From 1968 onwards Hellenic College, a liberal arts undergraduate school, also operates on the same campus. In 1944 the Archdiocese established Saint Basil Academy in Garrison, NY, a home for children in need. It was established in 1944 to house orphaned children and later became a school to educate young Greek women to teach the Greek language in parish communities. Today it is a safe haven for children within a nurturing and spiritual environment.

When Greece entered World War II on ‘Oxi’ Day, October 28, 1940, rejecting Italy’s ultimatum which would have meant surrendering to the Axis forces, a group of leading Greek-Americans, headed by businessman Spyros Skouras decided to form the Greek War Relief Association (GWRA) and offer aid to Greece. Significantly, they turned to Athenagoras for his blessing and support and the first meeting took place at the Archdiocese with the Archbishop presiding. Throughout the Greek-Italian war of 1940-41 and the following years when Greece fell under the occupation of the Axis, the GWRA was very active, with Athenagoras playing a leading role and local parishes organizing local drives to gather funds and materials for Greece.

In November 1948 Athenagoras was elected Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. This was the era of the Cold War and there was great concern about the influence of the Soviet-controlled Patriarchate of Moscow in the affairs of the Patriarchate in Constantinople. The role of U.S. President Harry Truman, with whom Athenagoras had a close relationship, was crucial in ensuring Athenagoras’ election. In 1949 Athenagoras traveled to Constantinople to assume his new position in Truman’s presidential airplane.

Archbishop Michael (1950-1958)

Athenagoras’ successor was Archbishop Michael (Konstantinides) who led the Archdiocese until his death in 1958. Originally Metropolitan Timothy of Rhodes was elected but he passed away suddenly before assuming the position. Michael had served as the pastor of the church of St. Sophia in London between 1928 and 1939 and then was elected Metropolitan of Corinth. He had distinguished himself as a theologian and through leadership in pastoral matters. Michael arrived in the United States at a time when the Greek-American community was experiencing upward social mobility, was being assimilated in American society, and was achieving a position of respectability. Nonetheless, Michael succeeded in deepening the Church’s spiritual life and promoting the Greek language while also being able to adapt to the needs of the younger, American-born generation. He founded the very successful Greek Orthodox Youth of America (GOYA) organization in 1951, permitting the use of English in its meetings, and by 1958 there were some 250 parish-based groups. He also established a national Sunday School program with an all-English curriculum.

Where Athenagoras had introduced the ‘monodollarion’ (one dollar) contribution by each member of the Church, Michael introduced the dekadollarion (ten dollar) contribution and significantly improved the finances of the Archdiocese.

Noting the rising status of Greek-Americans in American society, and also aware that the United States was experiencing an era of increased religiosity, Michael worked towards gaining formal recognition for Orthodoxy as being the ‘Fourth Major Faith’ in America, along with Catholicism, Protestantism, and Judaism. Michael had completed his graduate education at a seminary in St. Petersburg, where he witnessed the events of the Russian Revolution which made him an outspoken enemy of communism. This helped Michael to continue the tradition of maintaining close relations with the White House that Athenagoras had established. President Eisenhower asked Michael to participate in his second-term inauguration and he offered the invocation there in January 1957, giving him the distinction of becoming the first Orthodox hierarch to take part in the Inaugural Ceremonies of a United States President.

At the very end of Michael’s tenure the Archbishop established an Old People’s Home in Yonkers, New York. Michael himself had offered the first contribution when the fundraising campaign began. It opened its doors in May 1958. Eight years later, Michael’s successor Archbishop Iakovos named the institution the St. Michael’s Home in honor of his predecessor and founder of the Home. In December of 2020 present-day Archbishop Elpidophoros blessed the laying of the cornerstone of the new modern building that will house the Home in Uniondale, Long Island.

Archbishop Iakovos (1959-1996)

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople chose Iakovos (Koukouzis) to succeed Archbishop Michael. Iakovos quickly established himself as the leading figure in Eastern Orthodoxy in America and as one of the most important figures in the history of the Greek-American community. He combined his pastoral leadership with an ethnarchic involvement in Hellenism’s national issues. By becoming involved in the diplomatic relations between Greece and the United States, Iakovos managed to become recognized as the representative of the Greek-American community and as a mediator between the community, Greece, and the United States. Born on the Aegean island of Imvros, Iakovos in his youth witnessed the handing over of the island to Turkey and that traumatic moment shaped his involvement in Greek-Turkish relations the rest of his life. In many ways, he filled the historic role of ethnarch that certain leaders of the Greek Orthodox church have played in the past. His actions created a great deal of admiration and also criticisms, but whatever one’s point of view, it is generally acknowledged that he enhanced the Archdiocese’s presence in America and contributed towards Orthodox unity in America by being one of the founders in 1960 of the Standing Conference of Orthodox Bishops in America (SCOBA). He was elected its first chairman.

Prior to arriving in New York as the new Archbishop, Iakovos had served as a cleric in the United States from 1939 to 1954, most of them as Dean of the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Boston, after which he served for five years as Patriarch Athenagoras’ representative at the World Council of Churches in Geneva. Thus, upon becoming Archbishop he possessed a wide knowledge of both Greek America and of world affairs.

Iakovos began his tenure in office boldly declaring that the Greek Orthodox Church in America was no longer an immigrant Church, and it should behave with the self-assurance of a mainstream church. It took account of the assimilation of Greek-Americans into American society but worked also to preserve the Greek language and ties with the homeland. He outlined his openness to work with the assimilated Greek Americans at the Clergy-Laity Congress in Denver in 1964. The following year he responded to the call to leadership on civil rights issues by the Reverend Martin Luther King and traveled down to Alabama. There, he became one of the few prominent non-Black clergymen to walk side by side with King in one of the famous civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery. In doing so he saved the honor of the Church and the Greek-American community because not only did no one else support him in his move but in fact he was heavily criticized at the time. A photograph of Iakovos next to Martin Luther King in Alabama that appeared on the cover of Life magazine captures the proudest moment in the history of the Greek presence in America. It should be said that Iakovos was by no means a radical – at the same time the Archdiocese was supporting the war in Vietnam.

When a group of colonels seized power in Greece in 1967 and established a junta, this did not prevent Iakovos from going ahead with the plan to hold the Clergy-Laity Congress of 1968 in Athens, where he was received with full honors by the regime. In 1970 the Greek state donated a parcel of land in the western Peloponnesos to the Archdiocese, enabling it to establish the Ionian Village, a summer camp for Orthodox youth. After five years of exchanges with the colonels and trying to act as a mediator between exiled Greek politicians and the colonels, who he was advising to step down but with no results, Iakovos turned against the regime. A letter he sent to the State Department in 1973 characterizing the regime as tyrannical was leaked to the New York Times and was published. In the twelve months that followed until the regime collapsed in July 1974 relations between the two sides were strained.

Following the end of the junta and the restoration of democracy in Greece in the wake of the Turkish invasion and occupation of the northern part of Cyprus in 1974, the Greek-American community rallied to the side of the Greek Cypriots. Several lobbying organizations were formed and within months their pressure – along with a broad-based antipathy to Henry Kissinger and his policies – persuaded the U.S. Congress to impose an embargo on the sales of U.S. arms to Turkey, which lasted until 1978. During that period one of the lobbying organizations, the United Hellenic American Congress, based in Chicago and led by businessman Andrew Athens, adopted Iakovos’ positions. Meanwhile Iakovos established himself as a mediator between Washington, DC and Athens and held several meetings at the White House and with Greek prime minister Constantine Karamanlis. Iakovos’ role as interlocutor with political leaders was due to the diligent work of his close associate, Fr. Alexander Karloutsos. This helped to reverse the negative image Iakovos had in Greece as a sympathizer of the junta that Greeks suspected had been installed by the CIA which led to left-wing newspapers to call him “CIAkovos.” Suddenly Iakovos gained widespread admiration instead for his leadership role and began being described as an ‘ethnarch;. In the United States as well his stature grew and in 1980 President Jimmy Carter awarded him the prestigious Medal of Freedom, making him the first Greek-American to receive such a high honor.

In terms of the affairs of the Church, the Archdiocese had experienced a serious crisis with a section of the Greek American-community in 1970 when at that year’s Clergy Laity Congress held in New York Iakovos made two bold recommendations, suggesting that the English language could be used at the Sunday liturgy in the case of a parish where knowledge of English was stronger than that of Greek among the parishioners. His suggestion was made within a broader context of the other recommendation, the need for the Archdiocese to begin making certain decisions on practical matters on its own, prior to consulting the Patriarchate. All this was greeted by a huge protest by the Greek language media in New York and many of the Greek-born community leaders in Astoria. Thanks to an opening up of American immigration laws, Astoria had become a flourishing ‘Greek town’ in Queens, New York because many new arrivals from Greece were settling there. In the end, Patriarch Athenagoras intervened and Iakovos appeared to back down, but in practice English began to be used more and more in liturgies in Greek Orthodox parishes across the United States.

In 1984 there were many events celebrating the 25th anniversary of Iakovos’ tenure as Archbishop. These events included being honored by the U.S. Congress, receiving an honorary doctorate from temple University in Philadelphia from the hands of its Greek-American president Peter Liacouras, a special concert led by Greek-American conductor Peter Tiboris, and an interview with the New York Times. Also in 1984, the organization Leadership 100 was created under the guidance of Archbishop Iakovos as an endowment fund of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese to provide an opportunity for Greek Orthodox leaders to support the life-sustaining ministries of the Church. Iakovos had already created the Order of St. Andrew of the Ecumenical Patriarchate through which the church honored Greek-American leaders by naming them ‘Archons’. Leadership 100, spearheaded by Fr. Karloutsos, was more explicitly established to create an endowment fund, with leading Greek-Americans pledging $100,000 donations to the church. Its founding members were Arthur Anton, Andrew Athens, Thomas Athens, George Chimples, Peter M. Dion, Michael Jaharis, and George Kokalis, all by now of blessed memory. It is testament to the significance of what has become an important institution of Orthodoxy in America that it still continues its work, currently under the expert guidance of its executive director Paulette Poulos.

In the 1980s there were more and more voices urging Iakovos to accelerate the process of the Americanization of the Church. What caused these voices to become louder were the declining numbers of intra-Orthodox marriages and baptisms throughout America. For example, in 1984 the number of baptisms, 8,109, was the lowest since 1961, and the intra-Greek Orthodox marriages, 1,821, were the lowest in the post-World War II era. Sociologist Charles Moskos and education professor James Steve Counelis were among several observers who were discussing the need for the church to adapt more quickly to the community’s Americanization. In 1988 an organization called Orthodox Christian Laity (OCL) was formed for the purpose among other things of working towards the establishment of an administratively and canonically unified, self-governing Orthodox Church in the United States. They were also among the first to make greater transparency in the Church an issue.

It was Iakovos’ own moves towards forging a Pan-Orthodox unity that led Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew to request and receive his resignation in 1996, after thirty-seven years as Archbishop. Iakovos and the leaders of the other Eastern Orthodox denominations in the United States met at the Antiochian church’s retreat center in Ligonier, Pennsylvania in 1994 to discuss the idea of greater pan orthodox unity in America. The prospect of such a process moving too fast and without the supervision of the ecumenical Patriarch led to Bartholomew’s dynamic intervention and put an end to that development. Another highlight of Iakovos’ tenure was when thousands defied the rain and attended a special farewell open-air liturgy held by Iakovos in Central Park in New York in the summer of 1996.

Archbishop Spyridon (1996-1999)

It would have been very difficult for any cleric to replace Archbishop Iakovos, and that also applied to Spyridon (Papageorgiou), Metropolitan of Italy whom the Ecumenical Patriarchate chose to replace the outgoing Archbishop. Spyridon was born in the United States but had studied in Europe where he had spent his entire clerical career. Ultimately Spyridon’s tenure was short because of a combination of reasons – his policies were considered too traditionalist and his style of governance did not sit well with many. A commission he created for the preservation of the Greek language headed by renowned foreign language teacher and Greek American John Rassias was one of the positive legacies he left behind.

At the time of Iakovos’s resignation the Ecumenical Patriarchate introduced a significant restructuring of the Orthodox Church in the Americas. The original Archdiocese of North and South America was divided into Archdioceses of Canada, South America, Central America and America (United States), and the regional bishops were upgraded to titular metropolitans and given greater autonomy from the Archbishop. The supervisory role of the Ecumenical Patriarchate over all those Archdioceses was strengthened.

Archbishop Spyridon’s tenure should not be considered a mere parenthesis in the history of Greek Orthodoxy in America. Nor should the difficulties he encountered be interpreted as having to do with his personality or his governing style. Instead, Spyridon embodied a traditional approach to the affairs of the Archdiocese, which ultimately proved to be unsuitable because the Church was already on the path of Americanization, leaving some traditional elements behind. The challenge of his successors would be to try and better balance between those two trends.

Archbishop Demetrios (1999-2019)

The next Archbishop was Demetrios (Trakatellis), the Metropolitan of Vresthena, a scholarly theologian who had taught at Harvard Divinity School. Demetrios, through his personality, was a calming influence on the affairs of the Archdiocese after a period of turbulence. Demetrios spoke about the need to cultivate a dynamic Orthodox faith in America, practicing love and philanthropy and strengthening the bonds of the Church with the human community. Very soon Demetrios had to deal with a set of more practical issues, aside from the ones that the Archdiocese was already dealing with which ranged from training new clergy to facing the difficulties of increasing secularism in America which also affected Greek Americans.

Immediately after the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001, that claimed the lives of almost 3,000 people and also destroyed the edifice of St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church which stood in the shadow of the World Trade Center, Archbishop Demetrios rushed to Ground Zero and offered prayers and blessed the ground were so many had died. In the following weeks he conducted memorial services and funerals for the victims of the September 11 tragedy, made repeated visits to Ground Zero, and affirmed the need to rebuild St. Nicholas Church. In December of 2001, the Archbishop spoke about the impact of September 11 on religious and social life at an international meeting in Brussels of more than one hundred Christian, Jewish, and Muslim leaders. The meeting was convened by Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew and Romano Prodi, President of the European Union.

Archbishop Demetrios also led the philanthropic responses to natural disasters, including the appeal for aid to Greece after the devastating fires in the summer of 2007. Likewise, in 2012 when the financial crisis in Greece became severe, the Archbishop initiated a campaign throughout the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America for humanitarian assistance to the people of Greece. It was conveyed through the Church of Greece and its philanthropic agency ‘Apostoli’. A similar project was also initiated in 2013 for humanitarian assistance for the people of Cyprus who were also faced with a severe financial crisis.

During Demetrios’ tenure the rich historical archive of the Archdiocese was organized systematically by Ms. Nikie Calles. The digital preservation of the Archives has been made possible through generous grants from the Niarchos Foundation, the Stephan and Catherine Pappas Foundation, and the Archbishop Iakovos Leadership 100 Endowment Fund.

The ongoing issue of the Archdiocese’s finances became weighed down by the complexities associated with a fund-raising campaign for the rebuilding of St. Nicholas. It was an ambitious and expensive plan that involved an internationally recognized architect, Santiago Calatrava, and was aimed towards not only recreating the Greek Orthodox Church that had been destroyed but also to create a ‘national shrine’ which was a sign of how Greek Orthodoxy considered itself, rightly, as an integral part of American religious life. The Archdiocese’s was assisted, where appropriate, by the generous help of Leadership 100 and a new organization named FAITH: An Endowment for Orthodoxy and Hellenism, which was designed to support programs for young people that promoted an understanding of Orthodoxy and Hellenism. Its original founders, who pledged $1 million each, were George Behrakis, Nicholas Bouras, George Coumantaros, Michael Jaharis, Peter Kikis, James Moshovitis, John Pappajohn, John Payiavlas, and Alex Spanos. But the financial challenges of the fundraising and the planning for the rebuilding of St. Nicholas proved too big a challenge for an Archbishop who was more suited to share his deep knowledge of theology than to be open to decisive decision making and managing a complex project. In 2019 Archbishop stepped down after twenty years of valuable service at the age of 91.

Archbishop Elpidophoros

If Demetrios’ election had been designed to calm the Archdiocese’s troubled waters, that of his successor Archbishop Elpidophoros (Lambriniadis) invited him to deal dynamically with the serious issues related to the rebuilding of St. Nicholas, of introducing overdue changes in the Archdiocese, and revitalizing the Church’s life. Elpidophoros, who had been born in Constantinople, was closely associated with the Ecumenical Patriarchate and had also taught at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. He received an enthusiastic welcome from the Greek-American community upon his arrival in the United States in 2019. As if he did not have enough of a task before him, Elpidophoros almost immediately had to deal with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic which created several controversies related to the ways Sunday liturgies would be conducted. Elpidophoros was clear and decisive, issuing a statement to the effect that “Science and our God-given reason demand that we employ every means available to protect ourselves and our families against the spread of COVID-19 and any other disease. In a crisis such as this, we need to exercise vigilance as a community, lest our churches become points of transmission of the disease.” Another unexpected issue was the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of several unfortunate instances of police violence against persons of color. In June 2020, at the invitation of the Borough President of Brooklyn, Eric Leroy Adams, who later became Mayor of New York, and Greek-American New York State Senator Andrew Gounardes Archbishop Elpidophoros attended a peaceful protest in Crown Heights, Brooklyn over the killing of Louisville EMT Breonna Taylor. In remarks following the march he said: “I came here to Brooklyn today in order to stand in solidarity with my fellow sisters and brothers whose rights have been sorely abused. This was a peaceful protest, one without violence of any kind, and I thank all of those involved, because violence begets only more violence. We must speak and speak loudly against the injustice in our country. It is our moral duty and obligation to uphold the sanctity of every human being.”

The centenary of the Archdiocese is certainly a momentous event that deserves to be honored and celebrated. Throughout its 100-year history the Archdiocese has managed to adapt to the changing circumstances in America and move forward. Orthodoxy is rooted in tradition and America stands for change, so it is not surprising that balancing between tradition and modernity poses a great challenge. It is that which the Archdiocese has to confront under Archbishop Elpidophoros as it enters the second century of its existence.

Alexander Kitroeff is Emeritus Professor of History at Haverford College in Pennsylvania.

NEW YORK – Meropi Kyriacou, the new Principal of The Cathedral School in Manhattan, was honored as The National Herald’s Educator of the Year.

MELBOURNE, Australia (AP) — More than 100 long-finned pilot whales that beached on the western Australian coast Thursday have returned to sea, while 29 died on the shore, officials said.

On Monday, April 22, 2024, history was being written in a Manhattan courtroom.

PARIS - With heavy security set for the 2024 Paris Olympic Games during a time of terrorism, France has asked to use a Greek air defense system as well although talks are said to have been going on for months.

PARIS (AP) — Paris has a new king of the crusty baguette.

WASHINGTON (AP) — A tiny Philip Morris product called Zyn has been making big headlines, sparking debate about whether new nicotine-based alternatives intended for adults may be catching on with underage teens and adolescents.